A wonderfully descriptive line from Keane’s - Somewhere Only We Know (see link in the Resource Section), might have come to mind when I recently dipped back into some rule books from yesteryear.

Two books, nostalgically important to me for different reasons, were sourced from the internet. The first Napoleonic Wargaming by Charles Grant (1974) in hardback and the second being Don Featherstone’s Battles with Model Soldiers (1970), which is in e-format for the Kindle.

One might suppose from this blog title that rose tinted glasses have transported me back to a ‘better’ wargaming time, but to be clear, I have not found this to be true and acquiring the titles has simply left me with a sentiment that wargaming has always been good and is very good today.

So this is just a rambling post that looks at those books in their 1970’s setting and how they read now, over 45 years later, set against a new generation of rules, that are equally sensitive to the value of playability and the joy of miniatures armies.

Please use the ‘read more’ tab for the rest of this post.

I look at the books with different eyes in 2019, but their importance to my own wargaming history in the 70’ is undiminished. They pressed the right buttons for this teenager all those years ago and kickstarted a life long passion for this hobby. This was all pre-internet when the fabric of hobby support typically relied upon a few magazines in the UK and one fanzine in particular, Featherstone’s Wargamer’s Newsletter. So these sort of wargame books, when they came along, were cornerstone items to the hobbyist of that era.

Considering their age, their prose is not as stilted as I recall, though the Grant book has a slight sense of that old fashioned BBC voice to it, but of course, that generation needed to be sufficiently ‘of the right stuff’ to get into print. By contrast, today, anyone can self publish or have an internet voice. To be fair, one our most modern and popular rule sets, Black Powder, seems to do quite well from its own dabble in a fake ‘gentleman’s prose’, which sometimes annoys me and at other times delights. This for example, concerning the Advanced Rules, just leaves me smiling every time I read it .. ‘they require a good working knowledge of the game and are therefore best digested at leisure in company with a good strong cup of tea’. What a fun sentiment.

Both books, typical of similar publications of their time, try very hard to construct rules set around strict parameters that centre on a precise application of ground scale, vertical scale, time scale, the pace that a soldier would march to and a proper representation of weapon ranges and their effect. There are pages of these real world influences being explained, which then get knitted into inter-related rules that preserve this ‘truth’ of real war performance. It seems important for the authors to demonstrate the integrity of their rules as properly reflecting the battlefield.

This seems a natural approach as those early wargame writers were typically men with a military background or an appreciation of the same, but perhaps more importantly, to the Airfix generation who had been brought up on box after box of 1/72 soft plastic soldiers, it was important to elevate the serious business of the wargame from the world of the ‘toy soldier’, which of course was reinforced by those moving from soft plastic to metal miniatures, something that of itself required a bit of money and gave the subject a note of seriousness.

While the exact pace of a soldier marching or the frontage a single man occupied was readily known and mattered, it is interesting to compare that design imperative to a more modern approach of ‘designing for effect’ an abstract way of just getting the feel of the thing right, without having to strictly underpin the design with real world constraints.

A good example of this can be seen in Grant’s Napoleonic wargaming. When it comes to shaking out a column into line, the main body uses the standard movement allowance so that each base can be measured out into their new position. The flank companies have further to travel travel to get into position and are given a higher movement allowance so that they can be measured into their new positions. Trade that off against the way Black Powder does exactly the same thing. They simply just have a formation ‘move’ in which the command base stays in position and the remaining bases are simply lifted and re-configured around the command base to show the new formation, making a very easy transition from column into line for example. The bottom line is that the effect is exactly the same, but the modern authors have not felt tied to copying actual military manoeuvres to get the same result. The evolution of such rule thinking is interesting on several levels, none of which matter really, it worked then and it works now, we have just got used perhaps to an easier route to reach the destination.

If we look at the intention behind the two books, Featherstone’s Battles with Model Soldiers was meant to be an absolute introduction to wargaming and as such, his rules here are even lighter than his other volumes. The book really does what it is supposed to do and holds your hand through a basic learning process. These days, rules without realising it, can make assumptions of the gamer having existing gaming knowledge and something that boasts to have just a few pages of rules, would indeed happily be a little longer, if only everything was explained in absolute fullness, to the satisfaction of a newbie, as Featherstone has done here in his conversational style.

In that regard, I admire his discipline, he must have been bursting to add more things in for a fuller gaming experience, but didn’t, sticking instead to his ‘starter book’ guns, something that Neil Thomas, a more modern rules author, has also managed to do with his fast play One Hour Wargames book, which has seemingly been ruthlessly cut to core mechanics.

Featherstone has given us an ACW scenario that is repeated three times, each time adding something new into the mix. It is played across a mostly open table, with a wall in the middle and a small woods out on either flank. It is in effect a symmetrical table, giving neither side advantage. In the opening version of the scenario, both sides get two infantry units each, then in the second scenario, one unit of cavalry is added to each side and in the final repeat of the scenario, each player gets an artillery piece a leader and simultaneous movement with written orders are introduced.

|

| An iPad adaption of the battlefield |

There is a blow by blow account of how the turns play out, with some serious hand holding, but one has to cast their mind back to that time when the explosion in wargaming was happening and there was a big potential ‘first time’ gamer audience, who needed plenty of help and it was something that clearly worked for me, as general wargame principles become embedded, making moving on to more sophisticated works much easier.

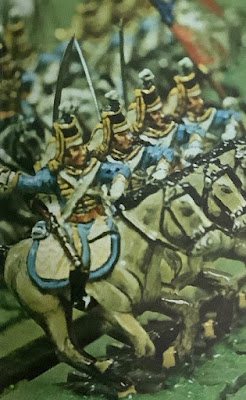

Grant on the other hand, in his book, is writing (much as Featherstone has also done in other works) to an audience that is already versed in the mechanics of wargaming and I loved every page of this, as he sets out to explain the napoleonic period and gives rules along the way that meet those descriptions. This was the age of the mostly black and white illustrated book, but there were some coloured plates in his book and as I revisit them now, one in particular I have clear memories of ... ‘the sight to stir every wargamer - hussars in full cry’

|

| Hussars in full cry! |

Grant’s book gently meanders through the various aspects of napoleonic warfare, adding rules along the way and justifying them in the text, then at the end of the book, all those rules are summarised into one place. The casualties on the musketry fire table are fixed, based on figure numbers firing, set against the range. As a randomiser, two differently coloured dice are rolled, one representing negative and the other positive. If there is a difference in their rolls, then the number of casualties is adjusted by either +1 or -1 as appropriate. I have always liked these sort of ‘old school’ arrangements and the use of Average Dice (not used here) and ‘bounce sticks’ to represent the travel of artillery shot is something I could easily slip back into.

The rules are pretty comprehensive, covering morale, line of sight and orders, plus the chrome type rules for things like shrapnel, canister and recalling charging cavalry and so they are quite comparable to what we are using today in that regard.

Interestingly, today, if I were to reach for two modern books that encompassed the same areas of influence as the two Grant / Featherstone books. I would take Neil Thomas’ One Hour Wargames or perhaps more specifically, step up to his Napoleonic Wargaming volume to do the job that the Featherstone book did, while probably going for Warlord Games’ Black Powder rules for the type of game that Grant espoused. This self selected pile of four books leaves me feeling that today, we have more in common with the 1970’s wargame scene and the thinking by those that set the hobby foundations, than we might generally assume in our ‘newer is better’ imaginings.

Where there are differences, it is largely to do with the modern sets taking a more relaxed approach to how formations move and how movement, weapon ranges and the representation of time only loosely relate to each other. Rather than highlighting that a man may need 24” of space when working out the battalion frontage and that the ordinary infantry step was 75 paces, each of 30 inches, per minute, as Grant does, the Black Powder style has instead changed to an abstraction of exactitude, in which things just need to look and feel right. I like that looseness, but I have also enjoyed dipping back into the older volumes and seeing how precision was examined, explained and put into game terms, no doubt so that the player had a satisfying sense that things were being done right! In truth it was probably a necessary design step to get us to where we are today.

As to the title of this post - Oh Simple things, where have you gone? Seemingly, they have not gone anywhere really! It is more likely that diminishing grey cells, the lost capability to stand before a wargames table for four hours and the necessity of how long the family dining table can be commandeered, increasingly dictate the type and density of game rules that I lean towards these days.

|

| The 12mm game |

Anyway, it was of course necessary that I set up the Featherstone basic scenario. No doubt, it would have been one of my earliest, if not the earliest ‘official’ scenario that I ever used, taking my Airfix figures off the floor and onto a table .... for that more grown up game, you understand! It is also more than possible that I had my WWI Germans standing in for one of the armies, because I had four boxes of them! That sort of thing didn’t seem to matter so much then, not to me anyway, well it wouldn’t would it? I mean, my woodland was made from cotton wool sprayed with diluted green poster paint! (Oh simple things, where have you gone?).

As the scenario only has four units per side, in 12mm, I can put this onto a pinboard sized playing area and use half measurements. However, rather than following the course of that game, I thought it perhaps more interesting to have the e-ink take a single mechanic (fire) and highlight the differences between the four books mentioned so far.

|

| Perry 28mm showing off :-) |

So for the purpose of these examples, we have each regiment formed of 18 figures in two rows of 9, on a frontage of 6 inches (150mm). Their weapon is the rifled musket and both sides will be regular troops without any additional attributes and are set at 8” apart. Seemingly, the Confederates are posher than anything I had back in the day, with a casualty stand that show they already have 5 casualties (or hits!).

Featherstone’s Battles with Model Soldiers.

By the time we get to the third setting of his scenario, the rules are delivering simultaneous fire and written orders for movement. The sequence of play is Move, Fire and Melee and units may not fire if the have already moved that turn. Maximum range for the rifled musket is 24”, set against an infantry movement allowance of 12”. The author assumes 25mm figures on what I always thought was an unhelpfully sized 8’ x 5’ table! I recall, thanks to understanding parents, putting four 2’ x 4’ boards across the family dining table on lazy Sunday afternoons to get my close approximation.

His units comprise of 20 figures, so we will pretend our units have 20 figures each. For every 5 figures, the firer gets 1D6 Fire Dice, so our fresh Union regiment gets 4 fire dice (the Confederate unit would get 3 having already lost 5 men). The dice are rolled and each pip inflicts a casualty (one figure) on the enemy unit. Our shooting is at medium range, which reduces each dice score down by 2 (note, cover, if they were behind that wall, would further reduce each dice by 1 pip). The Union roll 6, 4, 3 and 2. each dice is reduced by 2 for the range, so the modified result is 4, 2, 1 and 0. So they inflict 7 casualties on the enemy regiment, who remove that many figures. Growing casualties will effect how many future Fire Dice a unit gets.

Surprisingly perhaps, morale checks are only taken after melee fighting, not when suffering casualties from fire. The morale mechanic is intriguing and wonderfully simple. Each side adds up how many figures are left in their respective unit and multiplies that figure by a D6 result. The loser breaks and runs away.

Grant’s Napoleonic Wargaming.

We are typically dealing with smoothbore musket here, as we temporarily step outside the ACW arena, but accepting that, we can still make comparisons with the other rules. A unit can declare that it will move up to 3” after firing, but by doing so, fires on a weaker fire chart. Maximum smoothbore range is 15”, set against an infantry movement allowance of 6”.

There are several fire charts for differing situations. We shall use the one that allows line infantry their ‘first fire’ which is slightly more effective. At 8” (the 5” - 10” range band), with 16 - 20 men, the fire will cause a fixed 4 casualties. We throw two different coloured dice to get a randomiser that may adjust the casualty score up or down by 1. Red (negative) die roll is 5, Blue (positive) die roll is also 5, so they cancel each other out and the 4 casualties are not modified in any way and so 4 figures are removed from the enemy unit.

Here, morale is more sophisticated and must be tested whenever suffering fire for the first time, whenever taking losses and when it is charging or being charged. In any case, a unit reduced to 50% of original strength, automatically retires from the field. There are 15 different modifiers in the test, so there is some depth here and the final score will determine how the testing unit behaves.

Neil Thomas’ One Hour Wargames.

The ACW rules are but 2 pages long and so this is a good modern attempt at doing what the Featherstone introductory rules did. Infantry can fire up to 12”, set against an infantry movement allowance of 6”. The sequence of play is Move then Fire, the author does not allow melee due to the tactical dominance of firepower in this era. Units that move cannot fire in the same turn. With an absence of melee, this ordering of movement before firing makes it harder to physically take ground. Mr. Thomas, thoughtfully, would like us to play our game in a user friendly 3’ x 3’ space.

The number of figures in a unit does not matter, it is the unit itself that has a fire factor allowance, which is the score of a single D6. This is halved if the target is in cover and increased by +2 if the firer is elite. Over a number of turns, units accumulate hits and units are removed from play once accumulating 15 hits. The system does not feature morale. It is an example of a rule system being pared back as far as possible for simplicity and is an interesting study for that alone.

Whether one feels they go too far will be down to individual preference and need. The Confederates fire, they already have losses, but that doesn’t effect their fire. They roll a D6 and score a 2. A marker is placed with the target unit to show that they have absorbed two hits, so we know they can absorb 13 more before being removed from play.

As a unit takes increasing hits, its performance is not diminished and since there are no morale rules, it can always do whatever the player wants. Unfortunately, this leads to units that are desperately close to their 15 hit level, being used for attack in an almost uncaring way, squeezing the last bit of value out of them before they disappear. I have adopted my own simple morale rules, so that this moment is more likely to be avoided.

Warlord Games. Black Powder.

The sequence of play is Move, Fire and Melee. The maximum range for a rifled musket is 24” and that is set against a standard movement allowance for infantry of 12”, but importantly in a single turn, a unit, depending how successful it is when rolling for command, might even be allowed to move 3 times in the same movement window, so potentially it could travel 36” over open ground in one go ...... or fail its command and not move at all!

There is a counter-balance to this, in that if a unit moves to contact, the defender does get a chance to interrupt the attacker and make defensive fire, so that a unit cannot just charge into contact over long distances with certain impunity to enemy fire. The rule book is quite sumptuous, but unfortunately (for me) emphasises a big table, in the realms of 12’ x 6’, in consequence, to use these nice rules in home settings, players can find themselves scaling back, by for example using half inches or centimetres instead of inches to get to a more familiar table size.

The Glory Hallelujah ACW supplement has a rule that states if a unit moves more than once (12”) in a turn, it cannot also fire, which is an effective rule for this system, that could enjoy wider application than just with the ACW period and I am partly surprised that it did not make the second edition as a standard rule change.

Our Confederates are average 1863 troops and there is a stats page that shows their abilities, which for firing, is typically 3D6 fire dice and they will hit on 4+. Today they roll 4, 4 and 2, so have inflicted 2 hits. The defenders can now re-roll those two hits and try to turn them into saves (reflecting their own morale), they need a 4+ on each to cancel them. They roll 6 and 1, so this cancels one of the hits. The final outcome is that 1 hit marker is placed with the target.

Two important factors for BP are that when firing, a roll of a raw ‘6’ will always inflict a disorder result, even if the defenders save against THAT roll and when a unit absorbs a number of hits equal to its Stamina, it will become shaken and for most units this Stamina level is around just 3 hits. Once Shaken, units start to roll on the Break Table when getting further casualties, which has a variety of outcomes, made worse by disorder and higher levels of casualty. Rolling on the Break Table can be a moment to hold your breath and wish for lucky dice, as units can leave the field. I like that emotional connection to a game.

It is interesting to see that the old school rules have some common core themes. Individual figures are important because their numbers determine the firepower of the unit and measure it’s losses, it is a good alternative to a unit dragging hit markers around with it. Play is simultaneous due to player actions being determined by written orders for individual units and the rules promote their accuracy / simulation credentials by showing the process of how the rules directly fall from an understanding of figure ratio, ground scale, time scale, weapon range, marching rates and other things such as known musket accuracy at 100 paces etc.

In contrast, the modern rules concentrate more on process, without needing justification as to why the process is a particularly accurate portrayal of the subject, rather, they are content that results simply ‘feel’ credible and that the change to separate player turns (away from simultaneous phases) ensures smoother flow of play and makes for a more solo friendly experience.

Goodness knows what Mr. Grant would make of his French Line being able to move 12” or 24” or 36” or not be able to move at all in the one turn on the whim of the dice (Command Roll). This total lack of deliberate and tight control over exactly what a unit can do on the field of battle, would no doubt unnerve his due diligence on the realistic capability as to what a man and his unit can do in a two minute bound of time.

Most notably, since the 70’s we generally seem to have moved from hard data performance based rules to softer command and control, activation, impulse based rules, freed up by a more liberal application as to how activity versus time is represented. But process aside, it strikes me that game outcomes and player engagement are probably similar to how they have always been. The getting there may be different, but things are still about moving, firing, charging and running away, as they always have been.

In 1970, wargaming was a just a game and in 2019, it still is!

Resources

Keane, Somewhere Only We Know. Video Link